In Chapter 3, one of the most important theorem in empirical process theory, namely, the Uniform Law of Large Numbers (ULLN), is stated and discussed.

Summary

If a function class $\mathcal{G}$ is said to satisfy the ULLN, then

$$

\sup_{g \in \mathcal{G}} \left| \int gd(P_n - P) \right| \rightarrow 0, \quad \text{a.s.}

$$

The ULLN means that the expected and empirical average become closer as the number of samples gets larger for any $g \in \mathcal{G}$,

which is explained in the following figure.

Compared with the (strong) law of large numbers: $$ X_n - \mu \rightarrow 0, \quad \text{a.s.} $$ ($X_1, \dots, X_n$ are integrable random variables whose mean is $\mu$), the ULLN imputes $\sup_{g \in \mathcal{G}}|\cdot|$, which means for all random variables the law of large number holds, intuitively. This theorem guarantees that we can rely on empirical average with a relatively large number of samples, as long as a somehow “good” function class $\mathcal{G}$ is used.

We are interested in sufficient conditions on the random entropy $H_1(\delta,\mathcal{G},P_n)$ (here “random” means the distribution is $P_n$ rather $P$) in order to have the ULLN, and actually the condition is $$ \frac{1}{n}H_1(\delta,\mathcal{G},P_n) \overset{p}{\rightarrow} 0, \quad \text{for $\forall \delta > 0$,} $$ with the “envelope condition,” which explained in the last part of this article. This entropy condition can also be interpreted as that entropy does not grow faster than linearly.

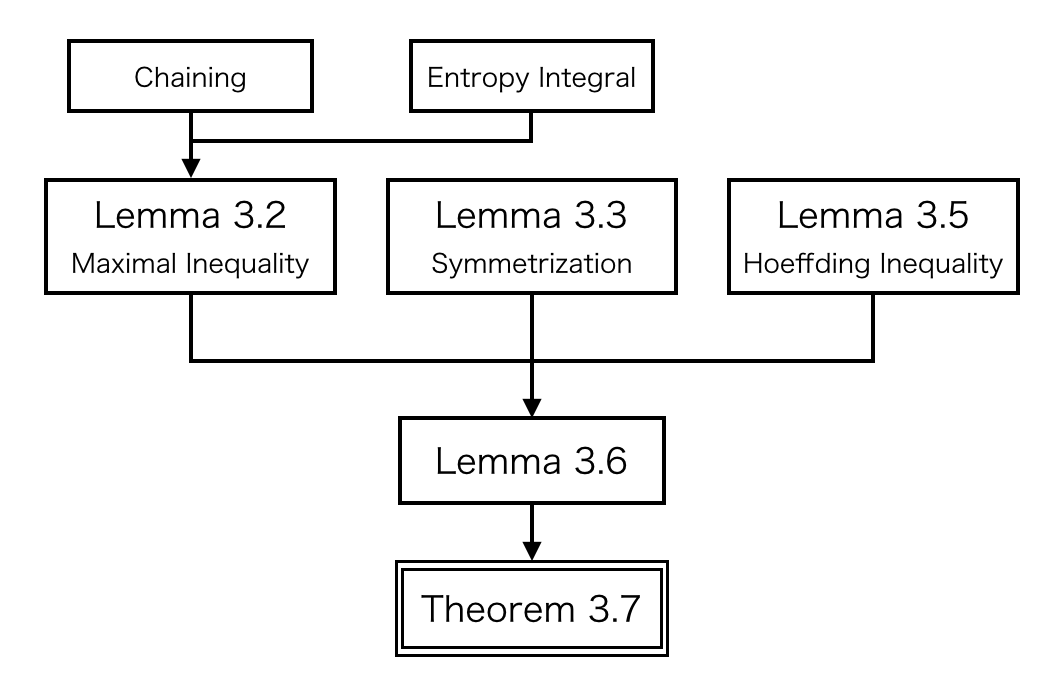

Techniques used in the proof is chaining and symmetrization, which often appears in empirical process theory.

In later parts, we are focusing on the proof of sufficient conditions for the ULLN. The main theorem is stated in the last part of this article, the section simply named “Uniform Law of Large Numbers.” If you are not interested in the proof details, you can skip to there.

Technique 1: Chaining and Entropy Integral

Let us begin with chaining technique, which is widely used in empirical process theory. If a given class $\mathcal{G}$ is finite, it is somewhat straightforward to obtain the uniform result. When a infinite class is given, i.e., the number of functions contained in $\mathcal{G}$ is over finite, we still get the same result by chaining technique, making finer and finer approximations of the class.

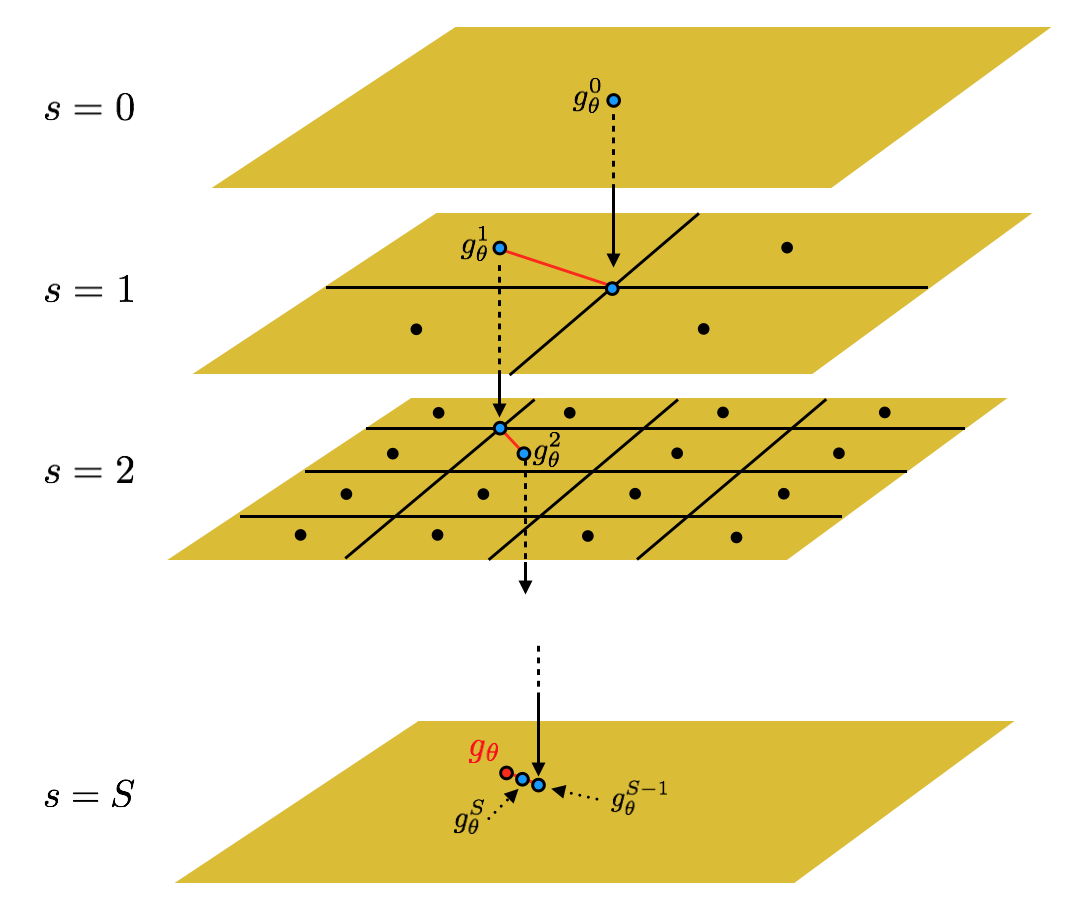

From now on, I formally state the chaining technique. Suppose that $\mathcal{G} \subset L_2(Q)$, and $\sup_{g \in \mathcal{G}}\|g\|_Q \le R$. For notational convenience, we index the functions in $\mathcal{G}$ by a parameter $\theta \in \Theta$ as $\mathcal{G} = \{g_\theta \mid \theta \in \Theta\}$. For $s = 0, 1, 2, \dots$, let $\{g_j^s\}_{j=1}^{N_s}$ be a minimal $2^{-s}R$-covering set of $(\mathcal{G},\|\cdot\|_Q)$. In other words, $N_s = N(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q)$, and for each $\theta$, there exists a $g_\theta^s \in \{g_1^s, \dots, g_{N_s}^s\}$ such that $\|g_\theta - g_\theta^s\|_Q \le 2^{-s}R$ (the definition of the covering set), where $g_\theta$ is regarded as approximated by $g_\theta^s$. For convenience, let $g_\theta^0 \triangleq 0$, since $\|g_\theta\|_Q \le R$. Then, for any $S$, $$ g_\theta = \sum_{s=1}^S (g_\theta^s - g_\theta^{s-1}) + (g_\theta - g_\theta^S). $$

As $S$ becomes sufficiently large, the second term in the RHS $(g_\theta - g_\theta^S)$ is small enough. The terms appearing in the first sum $(g_\theta^s - g_\theta^{s-1})$ can be made smaller as we choose appropriate $\theta$, and finally only involves finitely many functions (namely, $S$ functions).

Intuition of chaining is shown in the above figure. The covers for a given function class (yellow planes shown in the figure) become more and more finer as $s$ grows.

As stated in Chapter 2, entropy controls complexity of a given function, thus we want entropy, or covering number, not to be too large. In chaining technique, there are $2^{-s}$-covering sets for $s = 1, \dots, S$. Here what we need to suppress is the weighted sum $$ \sum_{s=1}^S 2^{-s} R H^{1 / 2}(2^{-s}R, \mathcal{G}, Q_n), $$ which can be understood as somewhat “volume” of entire covers, informally. The sum in this quantity can be replaced with an integral, under the condition of well-definedness: $$ \sum_{s=1}^S 2^{-s}RH^{1 / 2}(2^{-s}R, \mathcal{G}, Q_n) \le 2\int_{\rho / 4}^R H^{1 / 2}(u, \mathcal{G}, Q_n)du, $$ for $R > \rho$ and $S \triangleq \min\{s \ge 1 \mid 2^{-s}R \le \rho\}$. The RHS is called (Dudley’s) entropy integral.

This bound is said to be easy to check in van de Geer (2000)1 (P.29), but I don’t think so… A nice lecture note provided by Peter Bartlett2 (P.9) might be helpful to understand this one (but I haven’t gone through yet!!).

Maximal Inequalities for Weighted Sums

Next, we obtain an additional tool needed for the proof of the ULLN condition, maximal inequalities for weighted sums. Let $\xi_1, \dots, \xi_n \in \mathcal{X}$ be non-i.i.d. r.v.’s, and $Q_n$ be a empirical measure over them, i.e., $$ Q_n \triangleq \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \delta_{\xi_i}. $$ Let $W \in \mathbb{R}^n$ be a random vector.

Maximal Inequality If $Z_j$ (for $j=1,\dots,N$) satisfies $P(Z_j \ge a) \le \exp(-a^2)$, then $$ P\left(\max_{j=1,\dots,N}Z_j \ge a\right) \le \exp(\log N - a^2). $$

This is one of a basic concentration inequality (refer Lugosi et al. (2013)3). Now we extend this inequality for weighted sums. The extended one is not only applicable to the proof of the ULLN condition, but also to the variety of proofs appearing in later chapters.

Lemma 3.2 (Maximal Inequality for Weighted Sums) Suppose that for some constants $C_1$ and $C_2$, we have that for each $\gamma \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and all $a > 0$, $$ P\left(\left|\sum_{i=1}^nW_i\gamma_i\right| \ge a\right) \le C_1\exp\left(- \frac{a^2}{C_2^2 \sum_{i=1}^n \gamma_i^2} \right). $$ Assume $\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\|g\|_{Q_n} \le R$. There exists a constant $C$ depending only on $C_1$ and $C_2$ such that for all $0 \le \epsilon < \delta$, and $K > 0$ satisfying $$ \sqrt{n}(\delta-\epsilon) \ge C\left(\max\left\{\int_{\epsilon / 4K}^R H^{1 / 2}(u,\mathcal{G},Q_n)du, R\right\}\right), $$ we have $$ P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig(\xi_i)\right| \ge \delta \text{ and } \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_i^2 \le K^2\right) \le C\exp\left(-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2}{C^2R^2}\right). $$

The statement of Lemma 3.2 is a little bit lengthy, but the key point is that the probability of $\sup_gn^{-1}|\sum_i W_ig(\xi_i)| > \delta$ is bounded exponentially, under certain conditions. Let’s look through the proof of Lemma 3.2, noticing that the chaining technique plays an important role. Actually, the original proof in van de Geer (2000) omits a lots of details. I complements as much as I can.

Proof of Lemma 3.2 We take $C$ in a constructive way: take $C$ sufficiently large such that $$ \sqrt{n}(\delta-\epsilon) \ge \max\left\{ 12C_2\sum_{s=1}^S2^{-s}RH^{1 / 2}(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n), \sqrt{1152\log 2} C_2R \right\}. $$ Taking the maximum in order to “impute both conditions,” that is, $a > \max\{b,c\}$ implies both $a > b$ and $a > c$. Both conditions are used later, independently.

For $s = 0, 1, \dots$, let $\{g_j^s\}_{j=1}^{N_s}$ be a minimal $2^{-s}R$-covering set of $\mathcal{G}$. For $S \triangleq \min\{s \ge 1 \mid 2^{-s}R \le \frac{\epsilon}{K}\}$, applying Cauthy-Schwartz inequality on $\{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_i^2 \le K^2\}$, $$ \left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_i(g_\theta(\xi_i) - g_\theta^S(\xi_i))\right| \le K\|g_\theta - g_\theta^S\|_{Q_n} \le \epsilon, $$ where the last inequality holds from the definition of $S$, that is, we can obtain the last inequality as the cover becomes finer enough.

Then, the goal is to prove the exponential inequality for $$ P\left(\max_{j=1,\dots,N_S}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig_j^S(\xi_i)\right| \ge \delta - \epsilon\right). $$ Using the above inequality obtained by Cauthy-Schwartz, and the triangular inequality, this probability reduces back to the original target probability. Here chaining is used: $g_\theta^S = \sum_{s=1}^S(g_\theta^s - g_\theta^{s-1})$. By the triangular inequality, $$ \|g_\theta^s - g_\theta^{s-1}\|_{Q_n} \le \|g_\theta^s - g_\theta\|_{Q_n} + \|g_\theta - g_\theta^{s-1}\|_{Q_n} \le 2^{-s}R + 2^{-s+1}R = 3(2^{-s}R). $$ Let $\eta_s \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$ satisfying $\sum_{s=1}^S\eta_s \le 1$. Then (the following probability is the same with the goal because of the chaining) $$ \begin{aligned} P&\left(\sup_{\theta \in \Theta}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{s=1}^S\sum_{i=1}^nW_i(g_\theta^s(\xi_i) - g_\theta^{s-1}(\xi_i))\right| \ge \delta - \epsilon\right) \\\\ &\le \sum_{s=1}^SP\left(\sup_{\theta \in \Theta}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_i(g_\theta^s(\xi_i) - g_\theta^{s-1}(\xi_i))\right| \ge (\delta - \epsilon)\eta_s\right) \\\\ &\le \sum_{s=1}^S C_1\exp\left(2H(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n) - \frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2\eta_s^2}{9C_2^22^{-2s}R^2}\right), \end{aligned} $$ where the first inequality follows from the union bound, and the second from the combination of the maximal inequality and a result of the chaining $$ \sum_{i=1}^n|g_\theta^s(\xi_i) - g_\theta^{s-1}(\xi_i)|^2 \le n(3(2^{-s}R))^2 \le 9n\cdot 2^{-2s}R^2. $$ Say, from the first assumption of Lemma 3.2, we have $$ P\left(\left(\frac{\log C_1}{C_2^2\sum_{i=1}^n\gamma_i^2}\right)^{-\frac{1}{2}}\left|\sum_{i=1}^nW_i\gamma_i\right| \ge a\right) \le \exp(-a^2), $$ based on which we can state the maximal inequality $$ \begin{aligned} P&\left(\sup_{\theta\in\Theta}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_i(g_\theta^s(\xi_i) - g_\theta^{s-1}(\xi_i))\right| \ge (\delta-\epsilon)\eta_s\right) \\\\ &\le C_1\exp\left(2\log N_s -\frac{n^2(\delta-\epsilon)^2\eta_s^2}{C_2^2\sum_{i=1}^n|g_\theta^s(\xi_i) - g_\theta^{s-1}(\xi_i)|^2}\right). \end{aligned} $$ Note that the cardinality of $\Theta$ is $N_s$ by the chaining, and that $\log N_s = \log N(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n) = H(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n)$. I don’t know why there is a coefficient 2 in front of entropy.

Last task before concluding the proof is to choose an appropriate $\eta_s$. Let’s choose as $$ \eta_s = \max\left\{ \frac{6C_2s^{-s}RH^{1 / 2}(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n)}{\sqrt{n}(\delta - \epsilon)}, \frac{2^{-s}\sqrt{s}}{8} \right\}. $$ Then, by the choice of $C$, $$ \begin{aligned} \sum_{s=1}^S\eta_s &\le \sum_{s=1}^S\frac{6C_22^{-s}RH^{1 / 2}(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n)}{\sqrt{n}(\delta - \epsilon)} + \sum_{s=1}^S\frac{2^{-s}\sqrt{s}}{8} \\\\ &\le \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2} \\\\ &= 1, \end{aligned} $$ where the first inequality is from the union bound, and the second inequality is from $\sum_{s=1}^S2^{-s}\sqrt{s} \le 4$, which is shown in van de Geer and I omit here. From the definition of $\eta_s$, $$ \eta_s \ge \frac{6C_s2^{-s}RH^{1 / 2}(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n)}{\sqrt{n}(\delta-\epsilon)} $$ so that $$ H(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n) \le \frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2\eta_s^2}{36C_2^22^{-2s}R^2}. $$ Thus $$ \begin{aligned} \sum_{s=1}^S&C_1\exp\left(2H(2^{-s}R,\mathcal{G},Q_n)-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2\eta_s^2}{9C_2^22^{-2s}R^2}\right) \\\\ &\le \sum_{s=1}^SC_1\exp\left(-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2\eta_s^2}{18C_2^22^{-2s}R^2}\right) \\\\ &\le \sum_{s=1}^\infty C_1\exp\left(-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2s}{1152C_2^2R^2}\right) \\\\ &= C_1\left(1-\exp\left(-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2}{1152C_2^2R^2}\right)\right)^{-1}\exp\left(-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2}{1152C_2^2R^2}\right) \\\\ &\le 2C_1\exp\left(-\frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2}{1152C_2^2R^2}\right), \end{aligned} $$ where the first inequality is from just the above entropy bound, the second inequality comes from $\eta_s \ge 2^{-s}\sqrt{s} / 8$, the third equality is the sum of geometric series and the last inequality comes from the definition of $C$: $$ \frac{n(\delta-\epsilon)^2}{1152C_2^2R^2} \ge \log 2. $$ So far, Lemma 3.2 is proved.

Concluding remarks: Importantlly, since $\log N$ appears in the upper bound of maximal inequality, entropy is more common tool than covering number, I guess. That is, the logarithm of covering number governs the behavior of empirical processes. Actually, the combination of

- maximal inequality

- entropy

- chaining

are highly useful, as it can be seen from this proof.

Technique 2: Symmetrization

Symmetrized empirical process often becomes easier to handle, because the maximal inequalities for weighted sums can be used. More details about symmetrization are described in Talagrand & Ledoux (1991)4 (Chapter 6).

Let both $X_1, \dots, X_n$ and $X_1’, \dots, X_n’$ be i.i.d. r.v.’s follows a distribution $P$. $P_n$ and $P_n’$ be empirical distributions based on each pair of r.v.’s, respectively.

Lemma 3.3 (Symmetrization) Suppose that for all $g \in \mathcal{G}$, $$ P\left(\left|\int gd(P_n-P)\right| > \frac{\delta}{2}\right) \le \frac{1}{2}. $$ Then, $$ P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P)\right| > \delta\right) \le 2P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P_n’)\right| > \frac{\delta}{2}\right). $$

Since the proof of Lemma 3.3 is not hard to follow, I omit here.

Corollary 3.4 Suppose $\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\|g\| \le R$. Then for $n \ge 8R^2 / \delta^2$, $$ P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P)\right| > \delta\right) \le 4P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig(X_i)\right| > \frac{\delta}{4}\right), $$ where $W_1,\dots,W_n$ are Rademacher variables independent of $X_1,\dots,X_n$.

Proof of Corollary 3.4 $$ \begin{aligned} P&\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P)\right| > \delta\right) \\\\ &\le 2P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P_n’)\right| > \frac{\delta}{2}\right) \\\\ &= 2P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_i(g(X_i)-g(X_i’))\right| > \frac{\delta}{2}\right) \\\\ &\le 4P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig(X_i)\right| > \frac{\delta}{4}\right), \end{aligned} $$ where the first inequality is from Lemma 3.3, the second equality comes from the property of Rademacher variables. I don’t know why the last inequality holds.

Anyway, thus the tail probability of empirical processes is bounded by the tail probability of Rademacher averages, which can also be bounded by the maximal inequalities for weighted sums.

Uniform Law of Large Numbers

First, a stronger condition for the ULLN is shown.

Lemma 3.6 Suppose $\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}|g|_\infty \le R$, and $$ \frac{1}{n}H(\delta,\mathcal{G},P_n) \overset{p}{\rightarrow} 0, \quad \text{for $\forall \delta > 0$,} $$ then $\mathcal{G}$ satisfies the ULLN.

Proof of Lemma 3.6 Let $\delta > 0$ be arbitrary. By Corollary 3.4, $$ P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P)\right| > \delta\right) \le 4P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig(X_i)\right| > \frac{\delta}{4}\right). $$ By Hoeffding’s inequality, for each $\gamma \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and $a > 0$, $$ P\left(\left|\sum_{i=1}^nW_i\gamma_i\right| \ge a\right) \le 2\exp\left(-\frac{a^2}{2\sum_{i=1}^n\gamma_i^2}\right), $$ which holds because of $W_i\gamma_i \in [-\gamma_i,+\gamma_i]$, in precise way. I will not go in detail about Hoeffding’s inequality. Please refer to, e.g., Lugosi et al. (2013), or Section 3.5 of van de Geer.

Here, Lemma 3.2 holds for $K=1$, replacing $\delta$ by $\frac{\delta}{4}$ and $\epsilon=\frac{\delta}{8}$. Each assumption in Lemma 3.2 can be confirmed:

-

By Hoeffding’s inequality, $$ P\left(\left|\sum_{i=1}^nW_i\gamma_i\right| \ge a\right) \le C_1\exp\left(-\frac{a^2}{C_2^2\sum_{i=1}^n\gamma_i^2}\right). $$

-

By the assumption of this lemma, $\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\|g\|_{Q_n} \le R$.

-

By the conditioning below, $$ \frac{\delta}{8}\sqrt{n} \ge C\max\left\{\int_{\delta / 32}^RH^{1 / 2}(u,\mathcal{G},Q_n)du, R\right\}. $$

Thus, $$ P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig(\xi_i)\right| \ge \frac{\delta}{4}\right) \le C\exp\left(-\frac{n\delta^2}{64C^2R^2}\right). $$

Clearly,

$$

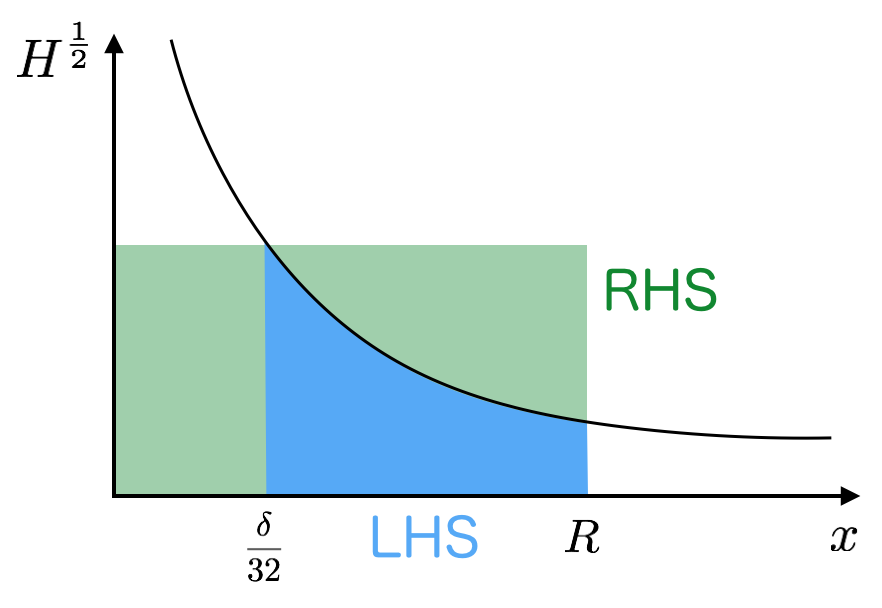

\int_{\delta / 32}^RH^{1 / 2}(x,\mathcal{G},P_n)dx \le RH^{1 / 2}\left(\frac{\delta}{32},\mathcal{G},P_n\right).

$$

I guess you can tell why the above inequality holds from the below figure.

Apply Lemma 3.2 conditionally on $X_1, \dots, X_n$, on the set $$ A_n = \left\{ \sqrt{n}\frac{\delta}{8} \ge C\max\left\{RH^{1 / 2}\left(\frac{\delta}{32},\mathcal{G},P_n\right), R\right\} \right\}, $$ then we find $$ P\left(\sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^nW_ig(X_i)\right| \ge \frac{\delta}{4}\right) \le C\exp\left(-\frac{n\delta^2}{64C^2R^2}\right) + P(\overline{A_n}) \rightarrow 0, \quad \text{a.s.} $$ I will add some complementary explanation. Let $E$ be the event appearing in the probability of the LHS. Then, $$ \begin{aligned} P(E) &= P(E \mid X \in A_n)P(X \in A_n) + P(E \mid X \not\in A_n)P(X \not\in A_n) \\\\ &\le C\exp\left(-\frac{n\delta^2}{64C^2R^2}\right) \cdot 1 + 1 \cdot P(\overline{A_n}). \end{aligned} $$ Thus the proof of Lemma 3.6 is concluded.

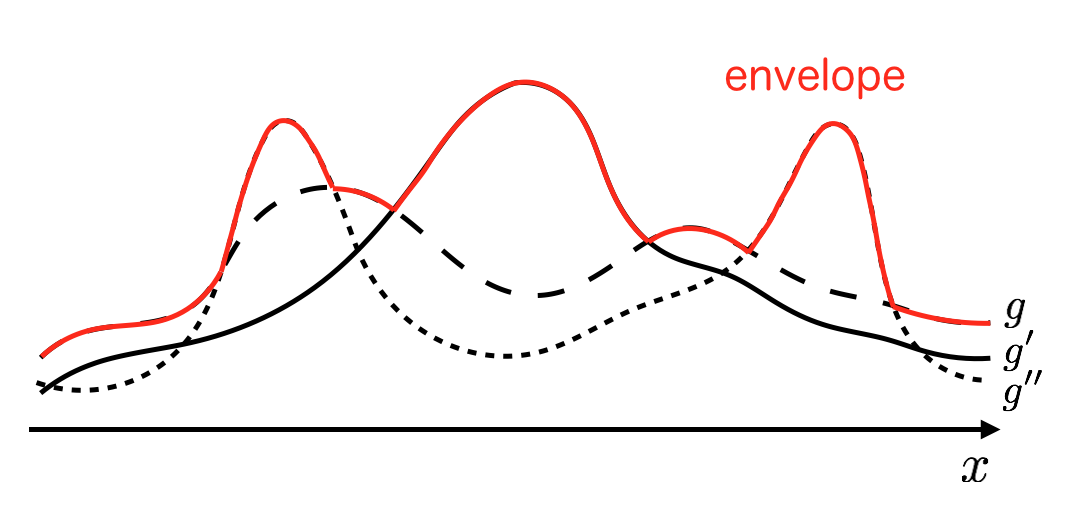

Now, let’s extend the result for a class of functions with envelope condition:

$$

G \triangleq \sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}|g| \in L_1(P).

$$

Theorem 3.7 Assume the envelope condition $\int GdP < \infty$ and suppose that $$ \frac{1}{n}H_1(\delta,\mathcal{G},P_n) \overset{p}{\rightarrow} 0, \quad \text{for $\forall \delta > 0$.} $$ Then $\mathcal{G}$ satisfies the ULLN.

Proof of Theorem 3.7 For each $R > 0$, let $$ \mathcal{G}_R \triangleq \{g1\{G \le R\} \mid g \in \mathcal{G}\}. $$ For each $g_1, g_2 \in \mathcal{G}$, $$ \begin{aligned} \int_{G \le R}(g_1 - g_2)^2dP_n &\le \int |+R - (-R)| \cdot |g_1 - g_2|dP_n \\\\ &= 2R\int |g_1 - g_2|dP_n, \end{aligned} $$ so $$ \begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{n}H_1(\delta,\mathcal{G},P_n) \overset{p}{\rightarrow} 0 \quad \text{for $\forall \delta > 0$} \\\\ \Rightarrow & \frac{1}{n}H(\delta,\mathcal{G}_R,P_n) \overset{p}{\rightarrow} 0 \quad \text{for $\forall \delta, R > 0$.} \end{aligned} $$ Therefore, by Lemma 3.6, the ULLN holds for each $\mathcal{G}_R$. Now take $\delta > 0$ arbitrary. Take $R$ sufficiently large (because $R$ is an arbitrary constant) such that $$ \int_{G > R} GdP \le \delta. $$ Next, take $n$ sufficiently large (based on $\varepsilon\text{-}N$ definition of limit) such that $$ \int_{G > R} GdP_n \le 2\delta \quad \text{a.s.} $$ (dirac masses not concentrated too much at the region $G > R$) and $$ \sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}} \left|\int_{G \le R} gd(P_n-P)\right| \le \delta \quad \text{a.s.} $$ (the ULLN holds for $\mathcal{G}_R$ thus we can take such sufficiently large $n$)

Then, $$ \begin{aligned} \sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int gd(P_n-P)\right| & \le \sup_{g\in\mathcal{G}}\left|\int_{G\le R} gd(P_n-P)\right| + \int_{G>R}GdP_n + \int_{G>R}GdP \\\\ & \le 4\delta \quad \text{a.s.,} \end{aligned} $$ where the first inequality is from the triangular inequality. This statement implies convergence in probability. Thus the proof of Theorem 3.7 is concluded.

My Questions

- Why is there 2 in front of the entropy in the exponential upper bound in the proof of Lemma 3.2? [here]

- The proof of Corollary 3.4 [here]

Please let me know if you have an idea.

-

Empirical Process in M-Estimation (van de Geer, 2000) ↩︎

-

(210B) Theoretical Statistics. Lecture 14. (Bartlett, 2013) ↩︎

-

Concentration Inequalities: A Nonasymptotic Theory of Independence (Lugosi, Massart & Boucheron, 2013) ↩︎

-

Probability in Banach Spaces (Talagrand & Ledoux, 1991) ↩︎